The world has been shaken a bit lately. Normal is no more. Our familiar activities had to be postponed. It might feel like chaos, but if chaos was a monster, what we have experienced in the past month is just the beginning of its awakening. Most of us hope that this monster will be lulled back to sleep again soon and governments are working frantically to re-establish the current order. Although we have not really tasted chaos, this time of uncertainty has given us a small insight into the events that have in the past escalated into an uncontrollable breakdown of all order.

It is this taster, this small insight into the origins of chaos, that I want to exploit to help us understand the environment in which many origin myths, and biblical texts, were written.

Most of us have been inconvenienced by new rules that restrict our movements, and communities have gladly complied because its for the greater good, and we still have all our basic needs met. Yes, many are concerned with the financial implications, both personal and the economy as a whole, but those factors have not been urgent enough to cause riots.

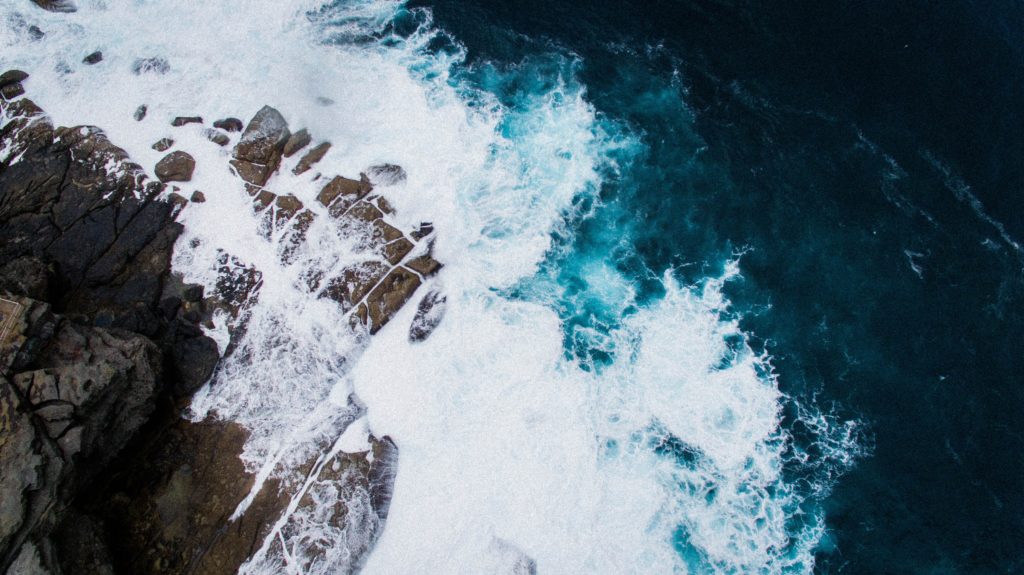

But imagine an ancient community in which shortages of food, disease, and conflict continue to build momentum. Arguments turn into acts of violence, and violence begets more violence. Now the monster of chaos is truly awake. All differentiation ceases. All that remains important is survival. It’s a war of all against all, or to say it another way – each man for himself, each woman for herself. Eventually the community faces total annihilation. Many ancient communities were destroyed because of this process.

But a solution presented itself. At the hight of conflict, where a war of all against all seemed inevitable, a new option emerged: a war of all against one. If the frustration, fear and anger of a mob could be turned and focussed on a minority group or an individual, the violence could be contained. A new form of violence, sacred violence, could redeem the community. Whether the victim was guilty or not, was not that important. To save the community was of utmost importance. The chosen scapegoat was sacrificed and functioned as a cathartic release for the community. And so the practice of sacrifice became a key ingredient in birthing more stable civilizations.

The people who wrote stories to celebrate the birth of these new civilizations, were the survivors. Their acts of violence were celebrated as heroic and justified by the invention of gods who demanded sacrifice. Many origin myths follow a familiar pattern: A monster of chaos threatens the total destruction of a world/society, but then a hero appears who through a creative act of violence kills the monster and saves the community. A new order of peace emerge; a new civilization is born.

These types of origin myths were written long before the Genesis accounts and were well known by the time Genesis 1 was written.

The author of Genesis presents a whole new vision of Elohim’s relationship to chaos. Following is an extract from the book “Creative Chaos” that explores this topic

Tohu Wa-Bohu

When God began to create heaven and earth, and the earth then was welter and waste [tohu wa-bohu] and darkness over the deep[Tehom] and God’s breath hovering over the waters.

– Genesis 1:1-2 RA

When God began creating … there was something already present: Chaos! What a peculiar thought. In fact, this idea is so perplexing that volumes of theories would be written to explain it away and to justify us overlooking the chaos of verse 2 and hastily skipping to verse 3. It would have been so much simpler if God began creating by commanding “let there be light.” But there it is, right in the middle of God beginning to create and the first creative words spoken – chaos. Before a word is spoken, Elohim broods upon this depth of the unformed. What is happening here? At the very moment of creation, the ruach Elohim, the divine movements, vibrate upon the face of a chaotic depth.

But Rashi, a 10th century Rabbi, translated this verse as follows:

At the beginning of the creation of heaven and earth when the earth was without form and void and there was darkness … God said Let there be…

His argument, which many translators are now supporting, is that the beginning is a subordinate clause to the act of creation that begins when God speaks. In other words Genesis 1:1 is not the first act of creation but rather it is in verse 3 where God speaks for the first time. It seems that chaos is the raw material from which the created order emerges.

Why has it been easier to imagine God creating out of nothing than God creating out of this chaotic depth? What is it about chaos that has evokes disgust and inspires fear? Since the earliest myths humans told, chaos has been associated with crisis, with evil, and with monstrous destruction. Our experience of chaos is seldom pleasant. Rather, we associate it with things falling apart, with confusion and with destruction. As such it became the enemy – the dragon that devours. And this mythic understanding of chaos has certainly found allies in some forms of Christian theology. Karl Barth, for instance, describes the chaos as that which God negated, worse than nothing, from which nothing good can come.

Could it be that the author of Genesis is beginning to subvert the myth of chaos? Have we misunderstood the tohu wa-bohu? Maybe we have feared it the way we fear the unconscious. We avoid this depth for it does not subject itself to control; it does not follow the patterns of our conscious logic. And if God is only perceived from the perspective of the conscious self, then we imagine a God of control, of mastery and of order – not a God in relationship with chaos. Like Jacob, we have no desire for the untamed wildness of Esau. We want a God as ordered, civilized, self-sufficient and conscious as ourselves. We would rather run and pretend that Esau does not exist than acknowledge this relation to the untamed other.

But God is more than what we can fit into our conscious frameworks. He is more than what is known and ordered. This God is present too in the unknown, the unordered, the unformed, the unexplained, the unpredictable and the unconscious. This God is not obliged to validate our order or submit to our reason. Yes, a distinction is made between Elohim and tohu wa-bohu, but God shows no aversion to it. Rather, there seems to be a mysterious attraction. Is there a part in God over which God exerts no control? Could chaos, in similar fashion as Esau, be a relation rather than an enemy? We seldom stand amazed in front of the expected order, rather it is unexpected chaos that astounds us. The kind of order in which chaos is an enemy, becomes oppressive, manipulating and ever more rigid. It soon loses whatever semblance of beauty it had. The only way in which order can retain its beauty is by embracing chaos as a friend. This kind of order acknowledges that it originates in and is composed of chaos. And it is in nurturing this playful relationship that new meaning, new beauty, and renewed order is possible.

Those who study these ancient texts have noticed the similarities between the first few verses of Genesis and the myth of Enuma Elish. In fact the very meaning of the words Enuma Elish is: “When in the beginning,” an almost identical starting line to the first verse of Genesis. The connections become even more astounding as we follow the story further. In this myth it is the chaotic waters, personified in the female face of Tiamat, that need to be overcome by the violent evil wind of Marduk. In Genesis we have chaotic waters, we have a wind, and we also have a face upon these waters. What we translated as “the face of the deep” is in Hebrew “the face of Tehom” – the Hebrew equivalent to Tiamat. In the Hebrew language it lacks the definitive article ‘the’ and therefore is used as a proper name (“The face of Tehom” vs “The face of the Tehom”).

Do you recognize the unconscious matrix of the text? The Genesis creation account is written over the unconscious text of many myths. The same signifiers are present, but the meaning is transformed as new relationships are formed between these signifiers. The God of Genesis does not need violence to defeat an evil formless chaos; rather his breath silently hovers, whispering possibilities of beauty and life. Can we recognize what it is within this formless depth that attracts the spirit of Elohim? The tohu wa-bohu is more than the opposite of order – it’s a different kind of order. It is more than nothing, it’s the possibility of everything.

Remember, this watery depth is not the seas, for they were created on the third day. The book of Job perceives this depth as a watery womb from which the seas were born.

Who hedged the sea with double doors, when it gushed forth from the womb. when I made cloud its clothing, and thick mist its swaddling bands?

– Job 38:8-9 RA

Creative Edge of Chaos

In the Hebrew Bible tohu is used to describe the desolate desert. The bohu is closely associated – a poetic twin (welter and waste) – and also refers to the uninhabitable nature of this wilderness. One Midrashic commentary translates it as “bewildered and astonished.” And in the Kabbalah, an ancient Jewish tradition of mystical interpretation, it is compared to Yesod hapashut (“simple element”), in which “everything is united as one, without differentiation.”

The compound tohu wa-bohu has more meaning than the individual parts. It adds a poetic rhythm; a repetition that introduces a slight variation; a nuanced meaning; a differentiating note. And as such, these reverberations harmonize with the vibrating wind (ruach) – the spirit that hovers over the waters.

Creation does not begin with self-sufficient power or authoritative words, but with a wordless hovering. It is in this contemplative silence that the possibilities within the chaos begin to dance. Tohu wa-bohu – a poetic echo in the silence: Elusive messages drifting; unlikely possibilities awakening; signifiers rearranging. With each repetition of tohu wa-bohu the surface grows more unstable. Possibilities vibrate. What might be nothing, murmurs of what might yet be something. And within the formless, patterns emerge. Creation is not the result of an enforced design but a willing response to divine seduction.

Tohu wa-bohu – these fluctuations intertwine with the movements of Elohim.

A breath, a whisper – and the depth begins to pulsate.

Suddenly the murmur finds its voice.

The surface of the concealment opens.

Light was hidden within the darkness, but now it is revealed.

These scattered messages might yet have meaning.

The in-distinction contains distinction.

The vibrations sift them apart.

There is a deep, deep pattern within the chaos, and with each differentiating echo the background noise finds a rhythm. This primordial drum-beat might yet be a symphony.

And God said… such simple clarity.

This voice was born from the endless echoes, the deep, deep yearnings of an abyss. Even at the heart of what is formless, there is a whisper of what is possible. This voice is not in conflict with the formless noise, neither does this order violate the chaos. Rather, it gives voice to its yearnings and draws forth its beauty.

And God said … and it was so.

The echoes in the deep reverberate to the surface and burst into creative voice.

The word and the act are one: “And God said… and it was so.”

Does the word precede the act of creation? Or does the process of creation give God a voice?

Elohim – the infinite possibility of everything – is actualized in part.

And so, in the first five days of creation, word and creative action flow together without any pause: And God said … and it was so. A new order emerges from the chaos.

But then… a new difference comes into play – life.

Then God said, “Let the sea swarm forth with swarming creatures” (1:20).

This is not the manipulative command of an autocrat, but the whisper of love, luring its creation, enticing her to bring forth the life and beauty that is latent in her. Creation happens not as an independent act of dominance but rather as a letting be. Again we see a God who makes creation possible, instead of than one who manipulates everything according to a predefined design. This God does not control the narrative but is the framework that makes meaning possible.

Another surprise… the crescendo of this symphony:

And God said, “Let us make a human in our image, by our likeness, to hold sway over the fish of the sea and the fowl of the heavens and the cattle and the wild beasts and all the crawling things that crawl upon the earth.”

And God created the human in his image, in the image of God He created him, male and female He created them.

– Genesis 1:26-27 RA

No longer is it a case of “And God said … and it was so.”

The seamless flow of word to action stops. A pause. A hesitation – an unstable fluctuation. A deeper echo interrupts the simple flow and from its center, a desire pulsates. The echo hears itself. From the unconscious potentiality, consciousness erupts. A new complexity is born in these words as language becomes self-reflective: “Let Us make man in Our image, according to Our likeness.”

It is this complex, echoing, self-reflective quality that is a unique aspect of human consciousness. The unformed possibility, the incomprehensible multiplicity that is Elohim, will be reflected in this being. Even the immeasurable depth of chaos will find a home in this new order. This new instantiation of consciousness will embody more than an instinctual echo – humanity will embody the unstable fluctuation from which untold possibilities could erupt.

In the creation of everything else, God could still be misidentified as a solitary entity acting upon a separate creation. But in the creation of humanity, the relational and reflective nature of God is revealed in the conversation with us – “Let Us.” Both the unity and multiplicity of God is revealed here. And this quality would be reflected in the creation of human consciousness, which is both a unified singular ‘I’ but consists of multiple relationships and voices. A desire is expressed within this relationship and it is in the creation of humanity where desire will find resonance.

If this primal chaos is not evil, not an enemy of God, but rather part of the process by which God creates, then this passage has great relevance to our present lives. For none of us began in a perfectly ordered and tranquil world. Neither is our internal world without chaos.

But it is in the middle of this mess, in the heart of chaos, that this God does his best work. In the midst of darkness there is a light that has not been snuffed out, a hope against hope, a grace that keeps pouring itself out into our existence. If we listen we can hear the whisper of desire saying: something truly new and beautiful is possible for you. This formless abyss can swarm with life. The illogical fragments, the residue of uninterpreted messages and repressed desires can be brought together in meaningful fulfillment.

“This is not the manipulative command of an autocrat, but the whisper of love, luring its creation, enticing her to bring forth the life and beauty that is latent in her. Creation happens not as an independent act of dominance but rather as a letting be. Again we see a God who makes creation possible, instead of than one who manipulates everything according to a predefined design. This God does not control the narrative but is the framework that makes meaning possible.” bEAUTIFUL!

Wow..this is so beautiful!

Pingback: Sermon, Jan. 10 | St. Dunstan's Episcopal Church

So disturbing and so beautiful at the same time!

Such a beautiful text.

Thank you for sharing

So we are like our Father, creator. We can go consciously into the tohu wa- bohu and create a new reality in our lives

What a beautiful glimpse into the heart of God!!!

This is perfect. And He said to Simon , who was Peter, flesh and blood has not revealed this to you but the Spirit of God.